She held on, going ever deeper underwater until, at some point, it occurred to her she’d better let go.

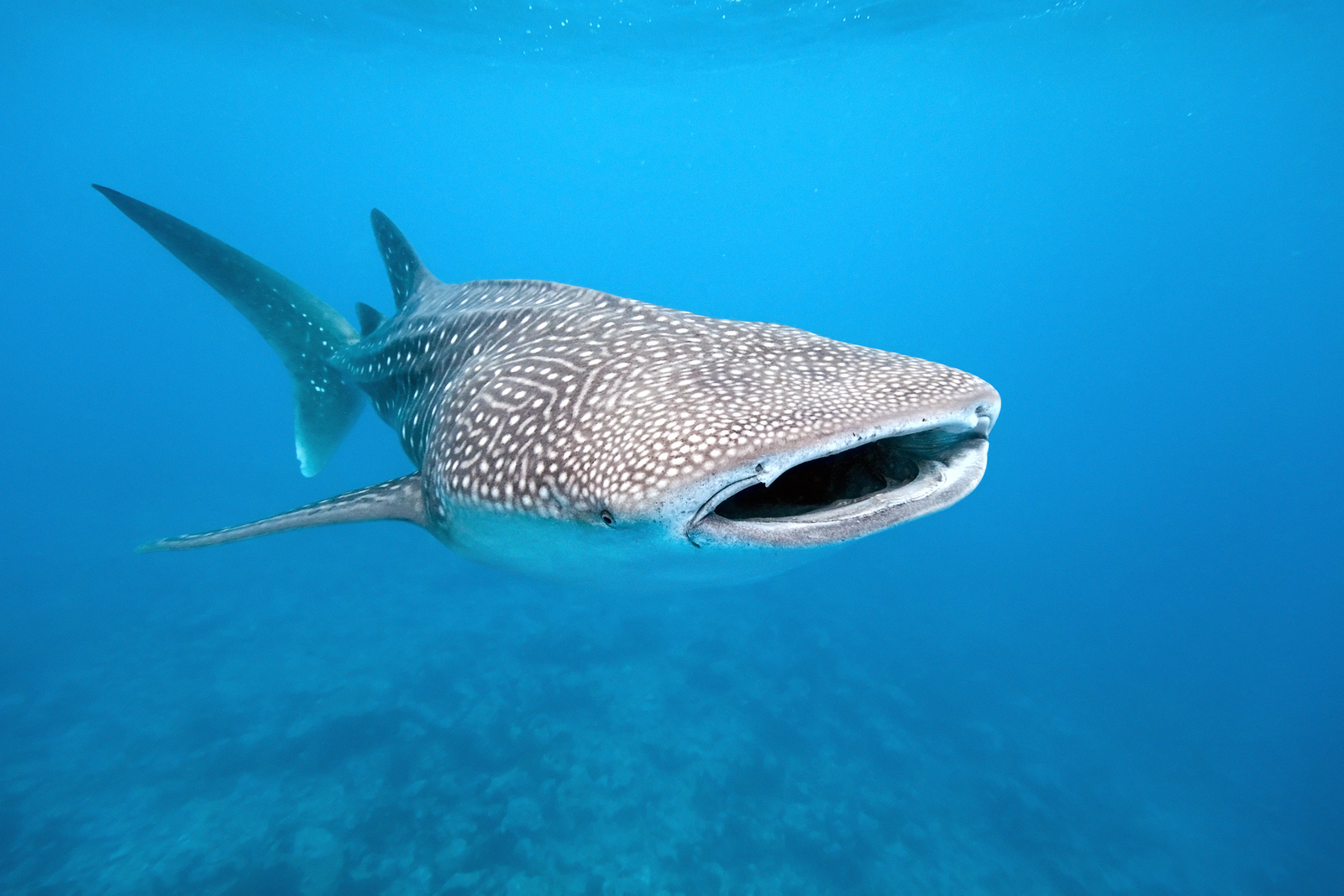

WHALE SHARK SKIN

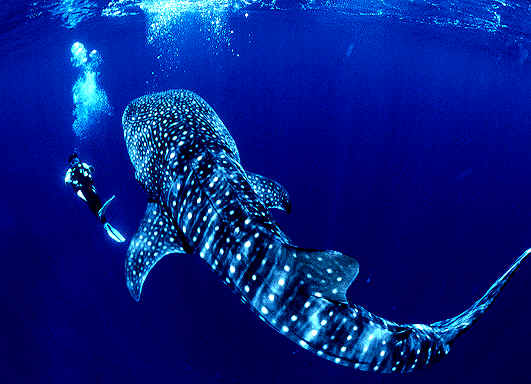

On one occasion, she grabbed the skin under a whale shark’s first dorsal fin as it cruised by. Once she began studying live ones, in the 1980s, she was hooked. The first whale shark she observed, in 1973, was a dead one caught in a net in the Red Sea. Everyone’s admitting they don’t know the answers, and everybody’s working together to get the answers.”Įugenie Clark is Mote’s founding director and one of the pioneers of shark research. Another type of electronic tag tracks a shark by transmitting location and temperature data to a satellite every time the animal surfaces.ĭespite all the new information, says Ray Davis, formerly of the Georgia Aquarium, “there are a lot of unanswered questions out there. The researchers have outfitted 42 sharks with satellite tags, devices that monitor water pressure, light and temperature for one to six months, automatically detach and float to the surface, then transmit stored information to a satellite scientists use the data to recreate the shark’s movements. “They don’t even flinch,” says Robert Hueter, a shark biologist at the Sarasota, Florida-based Mote Marine Laboratory, which collaborates with Proyecto Dominó. Researchers have fastened IDs to about 750 whale sharks here since the scientists started studying them in earnest in 2003, and they hasten to say the procedure does not seem to hurt the animal. The global whale shark population may number in the hundreds of thousands. No one knows for sure how many whale sharks are in these waters, but the best estimate is 1,400. The animals spend most of their lives in deep water, but they congregate seasonally here off the coast of the Yucatán, as well as off Australia, the Philippines, Madagascar and elsewhere.

The sleepy tourist island, whose primary vehicles are golf carts, has become a research center where scientists study whale sharks. But it is a shark-a kind of fish with cartilage rather than bone for a skeleton-a slow-moving, polka-dotted, deep-diving shark.ĭe la Parra and a group of American scientists set out this morning from Isla Holbox off the Yucatán Peninsula. A filtering apparatus in its mouth allows it to capture tiny marine life from the vast amount of water it swallows.

It’s named not only for its great size but its diet like some whale species, the whale shark feeds on plankton. The biggest fish in the sea, a whale shark can weigh many tons and grow to more than 45 feet in length. “Macho!” he shouts, having seen the claspers that show it’s a male. I hurry in after him and watch him release a taut elastic band on the spear-like pole, which fires the tag into the shark’s body. He slips off the fishing boat and into the water. De la Parra is the research coordinator of Proyecto Dominó, a Mexican conservation group that works to protect whale sharks, nicknamed “dominoes” for the spots on their backs. The information you submit will be used in mark-recapture studies to help with the global conservation of this threatened species.At the moment, Rafael de la Parra has but one goal: to jump into water churning with whale sharks and, if he can get within a few feet of one, use a tool that looks rather like a spear to attach a plastic, numbered identification tag beside the animal’s dorsal fin. You too can assist with shark research, by submitting photos and sighting data.

WHALE SHARK SOFTWARE

Cutting-edge software supports rapid identification using pattern recognition and photo management tools. The Wildbook uses photographs of the skin patterning behind the gills of each shark, and any scars, to distinguish between individual animals. The information you submit will be used in mark-recapture studies to help with the global conservation of these threatened species.

The library is maintained and used by marine biologists to collect and analyze shark sighting data to learn more about these amazing creatures.The Wildbook uses photographs of the skin patterning behind the gills of each shark, and any scars, to distinguish between individual animals. The Wildbook for Sharks photo-identification library is a visual database of various shark encounters and of individually catalogued sharks. You can help study sharks! Report your sightings

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)